Recently, I was introduced to Stephen Johnson’s work on “Where do good ideas come from” by a colleague of mine who wanted to help clients better understand Strategos’s thinking behind “crashing” during our ideation sessions. Johnson echoes our thinking through fascinating and thoughtful insights on how creativity is fostered. Johnson asserts that creativity loves connection; where creativity is not a singularity but seeks networks that offer fluid exchange and random collisions of thoughts and ideas. Take the English coffee house culture of the 17th century Enlightenment – one example being Lloyds Coffee House of London where merchants and sailors would gather and exchange ideas, which led ultimately to the creation of the insurance market, Lloyds of London and other related shipping businesses. TED could be considered a modern day version of that coffee house culture.

You may also be familiar with Tim Berners-Lee’s frustration with the arduous task of accessing scientific documents that led to his invention of HTTP in 1990. Not unlike the concept of the coffee houses where ideas collide and exchange, but on a global scale. Ideas love connection. Tim is now on a new quest to connect all raw data for his the next version of the Web.

As I stated, Stephen Johnson’s work is interesting to me because Strategos uses a similar concept of idea generation called “crashing”. During our ideation workshops, we “crash” different discovery insights together to develop new ideas. We actively exchange thoughts and ideas from different lenses by discussing customer needs, challenging orthodoxies, understanding our competencies, looking for discontinuous trends and learning from competitors and analogous industries. Then we “crash” insights from two different lenses to come up with never before seen ideas. Not unlike the lively English coffee house debates of the Enlightenment.

Where Do Good Ideas Go to Die?

There is no shortage of explanations on where good ideas come from but I am also interested in where good ideas go to die. Take, for instance, the steam engine. It was not invented in 17th century England during the Industrial Revolution. However, early accounts refer to an Aeolpile steam engine found in 1st century AD, Roman Egypt. Given this classical knowledge, why did it take until the 17th century for the Watt steam engine to emerge?

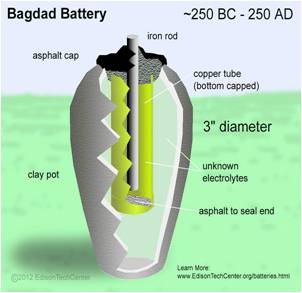

What about electricity? The electric battery was developed by the Mesopotamians; during the rein of Persian Empire over 2000 years ago. Yet, there is little evidence that the Persians built on their knowledge. How did this knowledge become buried?

Prior to the Industrial Revolution, according to William Rosen, the author of The Most Powerful Idea in the World, knowledge acquisition was a zero-sum game and expertise only lost value when it was shared. Worse, monopolies were only granted by monarchs and were often used as a powerful tool for revenue generation or as a reward for loyalty and support to the crown. But something changed…

You Can’t Share Something You Don’t Own

According to Rosen, it was the novel English concept of intellectual property ownership, and the sharing thereof, that eventually gave rise to and nourished the innovation during the Industrial Revolution. Not only was there an organic network of creativity flourishing in the coffee houses of London at the time, but now, one could own the ideas that those coffee houses fomented. In my opinion, this was the turning point and the reason why so many ideas came to life in this era. Ideas now had value and innovators had more motivation than ever before. The coin of the realm had become ideas.

At first, it was a slow start in England. Unscrupulous players tried to game the system and the application process for patents was onerous at best. Sound familiar?

And even though the UK and the Netherlands both had solid foundations in IP law, it wasn’t until the American Revolution that things really got rolling according to Rosen. The American Framers Benjamin Franklin (inventor), Thomas Jefferson (architect and designer) and James Madison advanced further intellectual property rights as distinct as tangible property rights. And by federalizing intellectual property laws, the Framers inadvertently created a more valuable patent system than the UK or the Netherlands who already had robust intellectual property law. According to Rosen, the same patent in a more populated country has more value due to sheer market size, thereby, attracting more innovation.

It was the ownership of intellectual property that enabled the Watt steam engine and served as the motivation behind the innovators of the Industrial Revolution. You see, each new innovation served as the basis for the next incremental innovation, all fueled by the ownership and sharing of intellectual property. This flipped the orthodoxy that acquisition of knowledge was zero-sum value, if expertise was shared. Ultimately, a patent is meant to be shared in return for a period of exclusivity.

Practical Applications

So, how can we apply this to today’s corporate environment? Can we motivate innovation through the ownership and sharing of intellectual property within an organization?

Let’s roll back to 2007 and look at the cell phone manufacturing industry during a time of great change and disruption. In 2007, Apple’s iPhone is challenging the status quo of industry orthodoxies, uncovering and satisfying latent consumer needs and thereby running away with the market. Great design, great execution, great retail environment, but in my humble opinion, that was just the price of admission.

I would propose that Apple’s innovation was not merely great design, great execution, great retail space and break through iPhone features that delighted consumers. These were must haves to play in this industry. To illustrate, compare the iPhone with the LG KU990 Viewty, released the same year in Korea. The Viewty is surprisingly similar. It can be argued that the Viewty had great design, an innovative touch screen, a superior camera, faster network connection and, unlike the iPhone, users could actually video chat. My Korean colleagues actually watched the 2007 World Series in Seoul on their phones…live! Heck, I still can’t do that in the Chicago in 2013. The iPhone’s success was not driven by the features alone.

Apple’s great innovation was their leveraging of their software developer kit. To me, it was a kind of intellectual property system built into the iPhone platform that democratized innovation for the masses. Anyone willing to purchase the SDK and put in the programming effort could own a part of Apple and share in the profits. Coupled with the sheer volume of devices, motivated developers to flock to the iPhone thereby releasing a land rush in iPhone app development. Google Android soon followed suit, dragging with them Samsung, Motorola, HTC, LG and others. LG still struggles in the smartphone market.

A side note: During my 5 years consulting in Korea, a colleague once confided in me that Koreans guard knowledge like gold something to be hoarded and seldom shared. I believe that concept is quickly changing and IP will become sacred in Korea. Again, in my opinion, this can be extrapolated to most of developing Asia. A country cannot copy innovation; it must foster it.

Another great example of democratizing innovation that is disrupting manufacturing is Quirky, albeit still in start-up mode. Quirky.com solicits ideas through its online platform and gives idea generators 30% of online sales and 10% of in-store retail sales, if the Quirky community decides to turn the idea into a product.

Threadless is a similar, more established company, concentrating exclusively on generating t-shirt designs. Threadless uses crowdsourcing for ideas but also for decision making. Threadless then pays designers whose work is printed $2,000 (via PayPal) and $500 in Threadless gift cards, which can be exchanged for $200 cash. Each time a design is reprinted, the designer receives $500.

So, the next time you think about giving your employees 20% free time, consider instead developing a formal network for them to share their ideas in return for joint ownership of the IP generated. I envision a network where ideas collide and are exchanged, where ideas can be jointly owned and where, ultimately, profits can be shared. And, if an employee chooses to leave, they continue their ownership of the IP. A platform that fosters a win-win for employees, corporations and the communities that support them will be sustainable (IMHO).